Skipping the Formal Tendering Process

There’s one way that’s superior to all, in terms of reducing the cost of bidding: That’s when you don’t have to bid at all.

And what could be better for a smaller operator than skipping the heavy investment of a formal tendering process (which, in some cases, rules the lower-tier player out of the game without the chance to even enter it)?

In my three-Part series you’ll find here on the Beating the Big Boys At Bids blog (Differentiating in A Highly Commoditised Space, Think from the Client’s Head, and ‘The Tangible Value of A Client-Focused Bid), I give an overview of how to avoid differentiate your organisation and your offering, based not on price but on a deep and well-researched client focus.

I also provide (in Part Three) a brief case example. In that example, I pointed out that the starting point for genuine client-centricity is the ability and willingness to (a) be humble, and (b) put the client first. Not just pay lip service to putting the client first but actually doing so – in every aspect of your research, your communications, and the formulation of your offering (all of which will ultimately show up in your end-submission . . . and that will be the topic of future articles).

The deeper you go into the research process (and most corporates don’t go very deep at all; they only think they do), the more immeasurably different you become, in the eyes of the client.

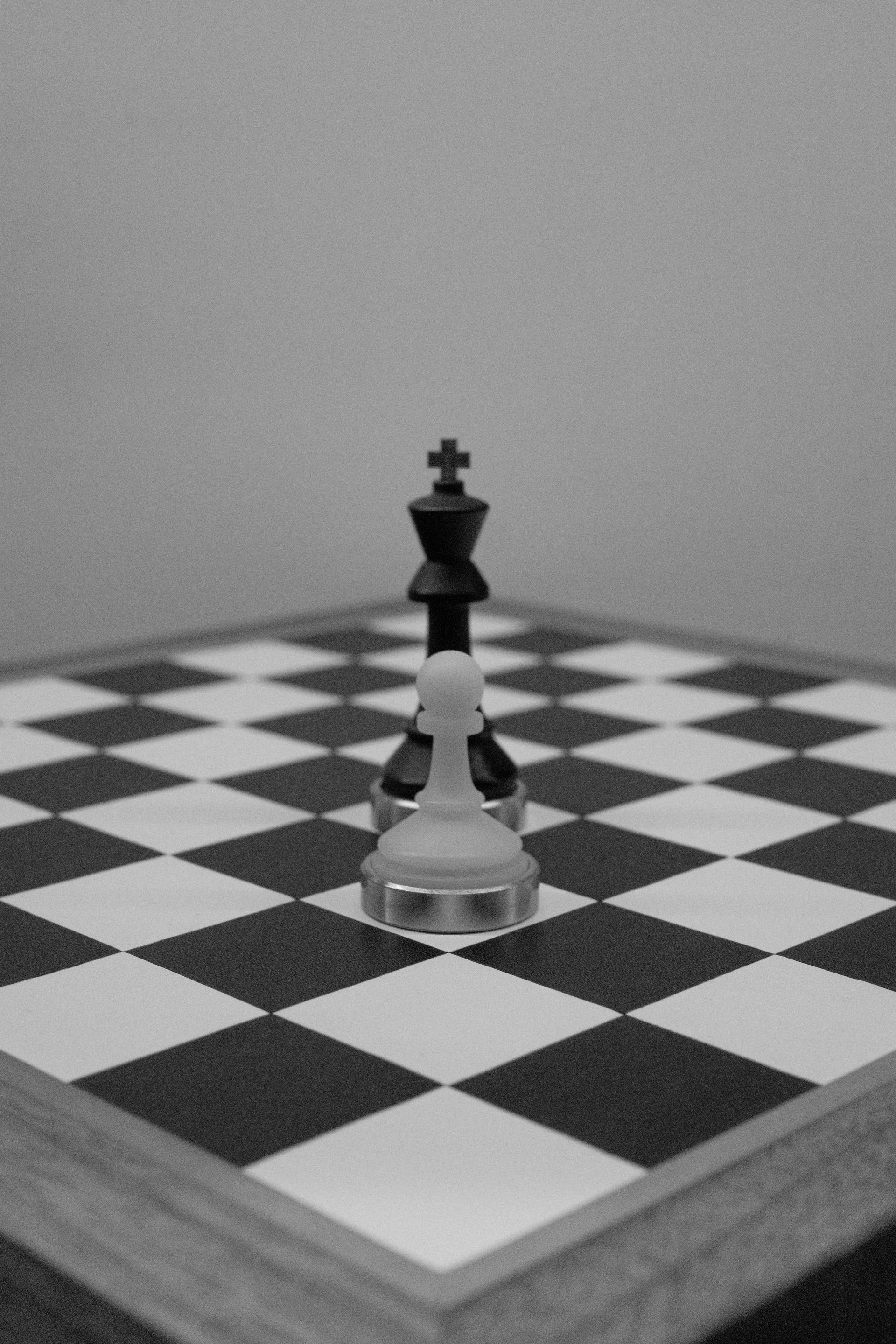

Imagine if, unlike your Tier One and Tier Two competitors (who have developed a mindset of reliance on their extensive libraries of templates and pre-existing material, which they readily succumb to the temptation to rely on after the tender release), your early and intense focus on the client and its world is so overt and obvious to that client, that it pre-positions you as a preferred relationship partner way before an EOI is even in formulation?

Arguably, the client and its evaluators would be anticipating the usual corporate same ol’, same ol’ template-style, supplier-centric dross from all Tier Ones (and Tier Twos), and it would be increasingly clear to them that they’re dealing with an entirely different class (albeit not size) of operator when it comes to you.

And so (if it’s within the client’s power) the seeds of an informal, sans-tender aware are sown.

Let’s map out a quick overview of what your cunning plan would look like.

In the case of a pursuit in which a formal tendering process is not yet a foregone conclusion, your best chance of avoiding it turning into one is to:

- Progressively formulate an offering based on an increasingly deep knowledge of the customer or client organisation’s specific environment, needs and circumstances (which involves quality questioning, deep research and formulation of the solution and strategy in incremental stages),

- Careful alignment of every aspect of the customer’s / client’s need with the strengths, and preferably, the uniquenesses, of what you are able to offer,

- A de-risked solution or proposition, and

- Real-time evaluation of any competitive threat and offering.

With the patience and tenacity to progress the pursuit in accordance with this strategy, you’ll stay close to the action as it evolves. You may even end up driving the action with the information the client sees you uncovering and the insights you’re producing.

And if you’ve made your offering a natural fit, your quality questioning will enable you to table all the right information, which – in turn – will support the drawing of the logical conclusions, in incremental stages, that a formal bidding process may be unnecessary . . . particularly if you have also identified and presented a maximally de-risked proposition.

More Insights & Intel